Keyboard Trigram Notation

Learn to play the piano with tablature

We are investigating how amateur musicians deal with conventional music notation. Some of the best musicians have problems reading regular treble/bass clefs and key signatures. We are interested in the potential of alternative music notations for piano based on the structure of the keyboard, with seven white and five black keys per octave. How do amateur musicians deal with such notation - especially older musicians? This has recently become an interesting question, given the increasing number of retired people and the importance of promoting their quality of life.

Can you play the piano but have difficulty reading piano music?

Many famous musicians could not read music. According to internet sources, these include Irving Berlin, Aretha Franklin, Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson, Tori Amos, Eric Clapton, Jimmi Hendrix, Lionel Ritchie, Taylor Swift, Bob Dylan, the Beatles and the Bee Gees.

Of course, all of these musicians could read music to a certain extent. At the very least, they could recognise the ascending and descending notes in the melody and the relative size of the intervals as they sang. But many of them didn't fully understand the more complex aspects of musical notation - which didn't stop them from composing and playing great music.

If you can't read piano music, you're in good company. This text is intended for musicians who - for whatever reason - are having trouble with the treble and bass clefs and their complicated sharps, flats and sharps.

A brief history of musical notation

Conventional Western musical notation is a great cultural achievement. It developed gradually over centuries and is used today to notate almost all (Western) music.

Accidentals are an important aspect. Accidentals are symbols that change the pitch of a note, usually by a semitone. Sharps (♯) raise the pitch and flats (♭) lower it. Sharps and flats remain in force until the next bar line. If you want to return to the original pitch beforehand, use a natural sign (♮). At the beginning of a line of notes you will often see a bunch of sharps or flats. This “key signature” determines the scale that remains throughout the piece or until a new scale or key signature appears.

When graphic musical notation emerged in the 11th century, there were no accidentals. Unaccompanied melodies in the 7-tone diatonic scale (ut re mi fa sol la si) were notated graphically on a staff by placing some notes on the lines and others in the spaces between them. This is how Gregorian chant was written down for the first time. Previously, it had been learnt by ear.

In the centuries that followed, the music became increasingly complex. After some time, all 12 notes of the chromatic scale could be notated. This was made possible by accidentals.

The notation used today was created around the 18th century. Since then, an astonishing amount and variety of music has been notated, which demonstrates the enormous flexibility of standard notation.

But modern Western standard notation is not necessarily the best solution for all applications. Take the guitar, for example. The relationship between what you see in a conventional guitar score and the way you place your fingers on the fretboard is very complex. That's why many guitarists use tablature, which makes it clearer where to place your fingers.

There is a similar problem with piano music. The relationship between what you see and what you do with your fingers is complex. If music notation had only been developed for the piano, it would look very different.

The problem with conventional notation for piano

On the piano keyboard, the note C always lies to the left of a pair of black keys.

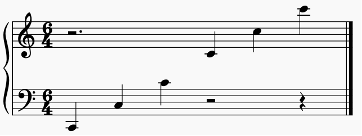

But in the musical score, the note C looks different in every octave register.

In addition, each note can be notated in at least two different ways, called enharmonic spellings. The note C sharp (C♯) can be notated as D flat (D♭). The note C can be notated as B sharp (B♯), C natural (C♮) or D double flat (D♭♭). The correct spelling depends on context and traditional rules, and is often ambiguous.

If you combine the first problem with the second, you can create 18 different notations for one and the same piano key:

All of these 18 notations occur frequently in real music. The more complex the music becomes, the more extreme the problem becomes.

Graphic piano tablature

Conventional music notation is sometimes called graphic because it resembles a graphical representation of pitch against time. Pitch corresopnds to the vertical axis and time to the horizontal axis.

Conventional music notation is also symbolic because it contains symbols that have special meanings. Pitch symbols include bass and treble clefs as well as accidentals (sharps, flats and naturals). Time symbols include time signatures, bar lines and note values (whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, etc.).

One way to make piano music easier to read is to make it more graphic and less symbolic - more like a graph. Pitch then corresponds more closely to the vertical dimension and time to the horizontal dimension. In the past, creative musicians did this in various ways and created notations that we might call graphic piano tablature. A tablature is a notation that is designed for a specific instrument, such as guitar tablature. In graphic piano tablature, the lines often correspond to the black keys and the spaces to the white keys.

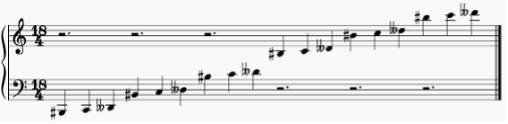

The version of piano tablature we propose here is called Keyboard Trigram because it is designed for the piano keyboard and based on a three-line staff (trigram). A staff is a group of parallel, evenly spaced horizontal lines. The five-line staff of conventional music notation is sometimes referred to as a pentagram.

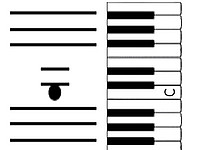

In Keyboard Trigram, the note C always looks like this:

The staff lines in the trigram correspond to groups of three black keys. The short lines (leger lines) correspond to groups of two black keys. On the keyboard, the note C lies to the left of a group of two black keys – right next to the lower one. In Keyboard Trigram, the note C lies below two leger lines, touching the lower one.

A modern piano keyboard has just over 7 octaves and includes 8 Cs. Americans call the lowest C “C1” (in German: CC) and the highest “C8” (in German: c5 or c'''''). C2 corresponds to the German C, C3 to c, C4 to c1 and C5 to c2. In the following, we will use the American labels. In keyboard trigram, these 8 Cs all look the same, apart from their position in relation to the middle of the keyboard.

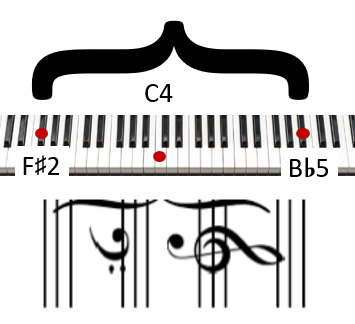

In conventional notation, the treble clef or staff is a pentagram (five-line staff) whose lines correspond to the pitches E4, G4, B4, D5 and F5. The treble clef symbol refers to one of these pitches: G4. Similarly, the bass clef symbol refers to F3. The same clefs can be used in keyboard trigram, for orientation. The inside of the curved part of the treble clef is aligned with G4, and the space between the two points in the bass clef is aligned with F3.

Keyboard Trigram offers an additional way to orientate yourself on the keyboard. The bar lines (the vertical lines between the bars) always cover the area you see above: the four groups of three black notes that are closest to middle C (C4). More precisely, the bar lines cover the range from F#2 (F♯2) to B5 (B♭5). The note C4 (c', middle C) is near the centre of each bar line.

Why learn piano tablature?

Alternative music notations have been around for a long time. In the past, people were reluctant to learn them because the available music was limited. Today, there is an almost unlimited supply of free piano music in electronic form – for example, as MIDI files on the Musescore platform. To take advantage of this, we have developed an app that can transcribe most MIDI files into Keyboard Trigram.

That now makes learning piano tablature worthwhile. Most music you might ever want to play can be transcribed automatically. Our app transcribes the most popular piano scores, whether classical, jazz, pop or something else. But it can't yet handle music in strange time signatures like 7/8, or music that changes from one time signature to another. We are working on it.

But many are still reluctant to learn piano tablature. They may argue that users of piano tablature will have to learn conventional notation sooner or later anyway. So why not learn it right away? In our experience, that this is not necessarily the case. Some piano tablature users will learn conventional notation later, others will not. When the advantages of keyboard tablature become clear and most music can be transcribed automatically, many will stick with tablature.

Piano tablature is primarily intended as a practical aid. But it is also theoretically interesting. It demonstrates that the rules of enharmonic notation (according to which F♯/G♭ is notated F♯ in one context and G♭ in another) depend on Guido's decision to use the diatonic scale as a reference frame for pitch notation. These rules do not directly influence the meaning or intonation of a note in a musical context, although they are indirectly related. Rather, the meaning and intonation of a note depend on its relationship to all other notes in its context. After all, the 12 semitones of the chromatic scale are approximately equal in size—an observation that originated not with J.S. Bach, but with the ancient Greeks. The assumption that the 12 steps of the chromatic scale are musically equally important regardless of their enharmonic interpretation in standard musical notation did not originate with Arnold Schönberg, but was widespread in the 19th century. The idea that musical intervals are not primarily Pythagorean numerical ratios, but learnt pitch intervals that arise in a complex, orally transmitted cultural context, is confirmed by 20th-century psychoacoustic studies on musical intonation as well as 19th-century studies of non-European music (see e.g. Alexander John Ellis; more).

How to use the piano tablature

To learn a piece in piano tablature, proceed as follows.

- Listen to a recording of the piece and/or the MIDI file from which the notation was created.

- Use the piano tablature to find the correct notes. Then imitate the sound of the performance.

- Check tone durations in the original notation. Mark important note durations by hand in the tablature, to remind yourself.

What is not notated in the piano tablature?

Our notation focuses on what most amateur pianists need to know: where to place their fingers on the keyboard.

To avoid clutter, we leave out the symbolic aspect of conventional rhythm notation. Instead, we mark bar lines (as solid lines) and beats (as dotted lines). We notate only the beginning (onset) of each note. The bar lines lie exactly on the note heads, whereas in conventional notation the bar lines are to the left of the first notes of a bar.

Users are free to add conventional rhythm notation by hand, if it helps. Sometimes, it helps to do this at selected points in a score, as reminders.

We have developed two different ways of using full and open noteheads.

- One is the conventional approach, in which full noteheads correspond to shorter notes (quarter notes, eighth notes etc.) and open noteheads to longer notes (half notes, whole notes etc.). In this case, if the composer notated a half or whole note, we use an open notehead; if a quarter note or less, we use a full notehead.

- In the other approach, full noteheads correspond to black keys and open noteheads to white keys.

In our app, you can choose between these two possibilities.

Our notation does not show which hand should play which note. Nor does conventional notation, in fact. Think of Bach fugues, where the inner voices may be played by either the left and right hand, and change from one hand to the other during the course of a melody.

You can add fingerings to Keyboard Trigram scores in the usual way.

Adding conventional rhythm notation

It is possible to add conventional rhythm notation to a keyboard Trigram score by hand. Simply copy the stems and beams from the conventional score.

To prepare a professional performance of a piece of music, you must first familiarise yourself with the original score. Firstly, clarify the duration of the notes by marking some of them by hand on the piano tablature as a reminder. This means copying note stems, beams and ties. You can also copy phrase markings. To avoid clutter, only mark the symbols you need to know.

If you are unsure whether or not to annotate your tablature, or how much to include, remember: historically, scores never included all the intended details of the performance. We are unsure what Mozart's or Chopin's performances of their own music sounded like, but we can be sure that these composers had many interesting but unnotated ideas about the performance of their works. The instructions on dynamics, rubato, pedalling and so on found in their scores often allow for a range of interpretations.

Advantages and disadvantages of piano tablature

The most important advantages have already been mentioned. Each octave register looks the same and there is a one-to-one correspondence between symbols and piano keys.

Space. The space the notation takes up on the page is similar to conventional notation. From bottom to top, it takes up more space, with 12 rather than 7 positions per octave. But from left to right, it takes up less space due to the absence of accidentals. Music that covers all seven octaves of the piano takes up more space, showing the relationship between the hands and the keyboard more clearly.

Complexity. Keyboard Trigram is suitable for both simple and complex music, and for both beginners and advanced pianists. The advantages become especially obvious for music that is highly chromatic or involves a lot of jumping around on the keyboard.

Is it okay to change a time-honoured musical tradition?

Many people ask themselves this question. In fact, we are not changing any tradition. Conventional notation is in no way affected by piano tablature, just as it is not affected by guitar tablature.

But some pianists are sceptical. Great composers wrote down their musical ideas in conventional notation. What would they have thought of keyboard tablature? In most cases, we'll never know, but imagine this: Maybe they would have liked a project that helps people play music they otherwise would not have been able to play. Composers are creative, innovative people. They like to experiment with new methods.

Some people worry about whether it's okay to leave out enharmonic spellings for the same key on the keyboard. Is it ok to write the tone F#/G♭ without reminding the reader that it was originally notated F# or G♭? Is something essential lost if we don't know the original notation? Musicologists and music theorists answer this question differently, but that is perhaps not the point. The point is that tablature does not aim to reproduce all aspects of the original notation. Rather, its aim is to help pianists press the right keys in the right order.

In any case, not everything is notated in conventional notation. It does not necessarily tell you how hard the individual keys must be pressed, nor the exact timing of pressing and releasing the keys or the pedal. Moreover, knowing about enharmonic notation will not help you become a great musician. But if you want to know whether you are playing a C# or a D♭, you can always look it up in the original score.

There is also an aesthetic aspect. Traditional notation is beautiful because it is familiar (we generally like familiar things, after all) and because we associate it with beautiful music. If you don't like Keyboard Trigram at first sight, the reason could be either a lack of familiarity or a lack of association between the look of the notation and the sound of good music. Your perception will change when you start using the notation.

Interested?

We want to know more about how pianists approach piano tablature. If you are interested, we would like to learn about your motivation, your musical background, the kind of music you want to play, what you need to achieve your goals, and so on. In order to answer these questions in a qualitative study, we are looking for participants who would like to take part in such an empirical study and who play the piano or keyboard by ear or cannot read conventional music notation.

Here is our offer:

- We will help you learn new piano pieces using piano tablature.

- We will keep confidential records of your progress and the various musical and other issues you raise spontaneously during the lesson. (We will not record interviews electronically unless you give us permission to do so.)

In a future scientific publication, the ideas we gain from the conversations with you will be anonymised so that you cannot be identified. The results of the study will help music educators to further develop and improve their approach to this type of teaching so that more people can enjoy playing the piano or keyboard.

At the beginning, we will ask you which pieces you would like to learn. We will then arrange a Skype call to introduce you to our notation of these pieces and help you get started. During the call we will both sit at the piano keyboard. Later we will talk again.

The project manager

Richard Parncutt is a retired Professor of Systematic Musicology at the Karl-Franzens-University Graz in Austria. As a musician (Bachelor of Music, University of Melbourne) he has often performed as a soloist (including three times as a soloist with various amateur orchestras). He enjoys writing and singing a cappella arrangements of pop songs (but with normal notation). As a music psychologist, he has published many works on the perception of musical structures, the origins of music and musical performance research, which are frequently cited. He was a member of the Music Notation Modernisation Association (MNMA) when it was founded by Thomas Reed in 1985 and is familiar with numerous alternative notation proposals.

Literature

Keyboard Trigram is presented on the MNMA homepage here:

https://musicnotation.org/system/keyboard-7-5-trigram-notation-by-richard-parncutt/

The general question of alternative notations and the advantages and disadvantages of "Keyboard Trigram" were discussed in the following book chapter:

Parncutt, R. (1999). Systematic evaluation of the psychological effectiveness of non-conventional notations and keyboard tablatures. In Zannos, I. (Ed.), Music and Signs (pp. 146-174). Bratislava, Slovakia: ASCO Art & Science. download

Examples

For examples of Keyboard Trigram, follow the links below.

Abbreviations: CN = conventional notation, KT = keyboard trigram.

- J. S. Bach: Minuet in G (BMV Anh. 114): CN KT

- J. S. Bach: Prelude in C: CN KT

- Beethoven: Moonlight Sonata, 1st movement in C♯ minor: CN KT; 3rd movement in C♯ minor: CN KT

- Dvorak: Humoresque in G♭: CN KT

- Rimsky-Korsakov: Flight of the Bumblebee in A minor: CN KT

- Satie: Gymnopodie No. 1 in D: CN KT

Are you looking for a specific piece? Write to us: parncutt at uni-graz.at

Automatic transcription

To transcribe your own sheet music, you need our app.

Our app is not error-free! But it transcribes most well-known piano pieces using MIDI files. The exceptions include:

- Pieces with complex time signatures such as 5/4 or 7/4. Simple, familiar time signatures such as 4/4, 2/2, 3/4 or 6/8 are ok.

- Pieces in which the time signature changes during the piece.

- Live recordings. The MIDI file must contain information about the original rhythmic notation and bar lines.

Our app takes a MIDI file as input and creates one graphic file per output page. Please wait until this process is complete. The graphic files are combined into a single pdf file.

- The app is called "KT_app_web". Download it here: zip.

- Click on it. There are three more folders inside.

- Click on "for testing", then on "readme.txt".

You will also need MATLAB Runtime version 9.9 (R2020b). It is helpful to know someone who knows this software.

Anyone who successfully transcribes their own notes with the app is asked to send the files to parncutt at uni-graz.at as a contribution to our open library.