Keyboard Trigram Notation: Readable tablature for piano

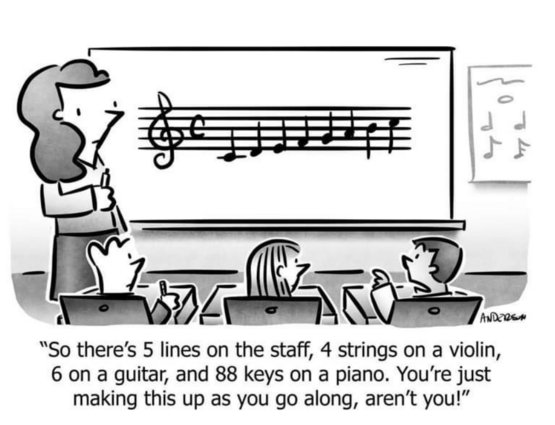

Can you play the piano, but can't read piano music? Are you having trouble with:

- the fancy symbols at the start of each line of music (treble and bass clefs), and their different meanings?

- the short lines above and below the clefs (leger lines)?

- the bunches of sharp ♯ or flat ♭ symbols that often follow the clef symbols (key signatures)?

- the task of remembering sharps and flats until the next barline, and then forgetting them?

- the natural ♮ symbols that cancel previous sharps or flats, and the double sharps and double flats?

- the piano keys that have two different names, like F♯ and G♭?

If you have the impression that conventional notation is overly complex, you're in good company. The list of famous musicians who could not (fluently) read music is long. It apparently includes Irving Berlin, Aretha Franklin, Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson, Tori Amos, Eric Clapton, Jimmi Hendrix, Lionel Ritchie, Taylor Swift, Bob Dylan, the Beatles, and the Bee Gees. Of course, all those musicians could see the notes going up and down in the melody as they sang, and the relative sizes of the intervals. But many of them did not quite get the more complex aspects of the notation – which didn’t stop them creating great music.

Introducing Keyboard Trigram notation

It is possible to read and play piano music without learning conventional music notation. Keyboard Trigram is a keyboard tablature -- a music notation that is specially designed for keyboard. Please check out our video.

The basic idea is this:

- On a regular piano or keyboard, the black keys are grouped into twos and threes.

- The long horizontal lines (staff lines) in Keyboard Trigram are correspond the threes. The short lines (leger lines) correspond to the twos.

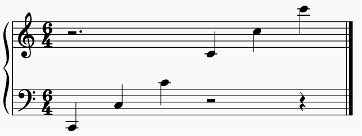

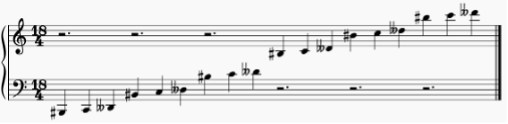

- In one style of notation (no. 1), black keys are notated with black (full) noteheads and white keys with white (open) noteheads. In another style (no. 2), black noteheads are used for shorter notes and white noteheads for longer notes, as in conventional notation. We offer both these options, and you can choose the one that you prefer. The following examples are in notation no. 1.

Sample pieces

Here are some examples of pieces in Keyboard Tablature. For each piece of music you can download three files:

- A file that allows you to hear the music (midi).

- A pdf file of the score in conventional notation (CN).

- A pdf file of the score in Keyboard Trigram no. 1 (KT).

J. S. Bach: Minuet in G - midi - CN - KT

J. S. Bach: Prelude in C - midi - CN - KT

Beethoven: Für Elise - midi - CN - KT

Beethoven: Moonlight Sonata 1st Movement - midi - CN - KT

Beethoven: Moonlight Sonata 3rd Movement - midi - CN - KT

Dvorak: Humoresque - midi - CN - KT

Rimsky-Korsakov: Flight of the Bumbebee - midi - CN - KT

Satie: Gymnopédie no. 1 - midi - CN - KT

How to transcribe any piece of music

Our app allows you to transcribe any piece of music that is available as a MIDI file into Keyboard Trigram. Here's how to do it:

1. Download MATLAB Runtime version 9.9 (R2020b) from <https://www.mathworks.com/products/compiler/mcr/index.html> and run it.

2. Download our app, which is permanently free of charge, and run it (<KT_app.exe>). It will take about a minute to load.

3. Find a good midi file of the music you want to play. Sometimes you can find midi files directly in Google. Countless midi files are available at MuseScore.org, but many are no longer free of charge. Please note that our project is independent of MuseScore or any other source of midi files.

4. In the interface for our app:

- Load the midi file. Wait for confirmation.

- Enter the time signature. You will find it at the start of the conventional score. It's the first two big numbers that you see (e.g. 4/4 or 3/4).

- Enter the duration of the upbeat, if there is one. For example, if there is a quarter-note upbeat, enter 1/4.

- Choose a notation style. "1" prints white keys as white noteheads, black keys as black noteheads. "2" prints long notes as white noteheads, short notes as black noteheads.

- Enter the name of the piece and the composer.

- Click on "convert" and wait for a few minutes, depending on the length of the piece. During that time, images of the pages of the transcription will pop up as separate figures. Ignore them.

- When final pdf appears (including the title you entered), save it. The file name will be the file name of the midi file plus KT (for Keyboard Trigram) and a number to distinguish successive versions.

If something goes wrong during conversion, close everything (using the task manager if necessary; reach it by hitting control-alt delete) and start again. If you spot an error in the final pdf (e.g., a missing note), try using a different midi file of the same piece.

If anything in this introductory text or the readme file is unclear, or the app doesn't work as it should, please contact Richard Parncutt (parncutt at uni-graz.at).

What is Keyboard Trigram?

Conventional music notation uses a five-line clef, sometimes called a pentagram. Keyboard Trigram has a clef of three lines that correspond to groups of three black keys on the keyboard. The short lines (leger lines) correspond to groups of two black keys.

Keyboard Trigram is like a graph of pitch (in semitones) against time (in beats). In our "no. 1" style, the onset of a tone played on a black key is a full notehead (round dot) and the onset of a tone played on a white key is an open notehead (circle). In "no. 2", a full notehead is a shorter note (quarter-note or shorter) and an open notehead is a longer note (half-note or longer), as in conventional notation.

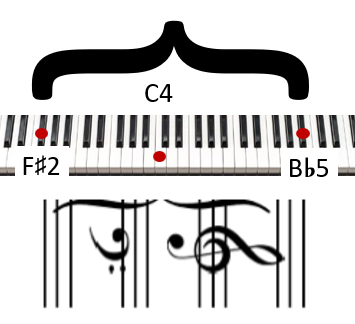

The vertical lines are barlines, and the dotted lines between them mark the beats within each measure. The barlines span a four-octave range: two octaves above and below middle C. Fun fact: that's the same range as Johann Sebastian Bach's clavichord and all his keyboard music. When a piece of music strays outside Bach's 4-octave range, extra clefs are added that lie outside the range of the barlines, using dotted lines.

That's basically all you need to know to read music in Keyboard Trigram. You can get started straight away. It's best to start with a piece that you have heard many times before and corresponds to your technical ability as a pianist.

Time signatures and upbeats

To use our app (see above), you will need to know the time signature of the music you are converting. The time signature is the two numbers at the start of the original score, just to the right of each clef.

Many pieces are in common time which means four quarter notes per measure (4/4). Others are in cut time (2/2). A waltz is usually in 3/4. Beethoven's famous Bagatelle No. 25 in A minor, commonly known as Für Elise, is in 3/8. Note that our app can only deal with more familiar time signatures. It cannot (yet) deal with not 5/4 or 7/4, or pieces in which the time signature changes.

You will also need to know if there is an upbeat or anacrusis at the start of the piece, and if so what its duration is. In most cases, there is no upbeat, so no action is needed. The upbeat of Für Elise is two 16th notes, which is the same as one eighth note. So you can enter either 2/16 or 1/8. Please enter upbeat information to the app for any piece that does not start at the start of a measure. Debussy's Claire de Lune is an example: the time signature is 9/8 and the duration of the first measure is 8/8. It is written with a 1/8 rest at the start of measure 1. To get correct results from our app in this case, enter an upbeat of 8/8.

You may be wondering why it is necessary to enter the time signature and upbeat, given that the time signature can usually be extracted automatically from the MIDI file. The trouble is, the upbeat often cannot be extracted from the MIDI file in this way. It is more reliable to enter it manually, and to do that you need to know the time signature.

Who can benefit from Keyboard Trigram?

Keyboard Trigram notation is for anyone who wants to learn to play the piano or keyboard without learning to read conventional music notation. That includes young people who are learning piano or keyboard from internet videos or apps. It also includes older or retired people have been wanting to learn piano for decades, or who want to take advantage of the benefits of music making for health and quality of life. Both groups can benefit from a notation that is based in a simple way on the structure of the piano keyboard.

Keyboard Trigram is also for expert and professional pianists who want to be able to visualize pitch-time patterns relative to the keyboard -- which fingers land on which black and white keys. This style of notation can help you learn and memorize new repertoire, and plan fingerings and interpretations, while still consulting conventional notation. Notational bilingualism is possible!

Whether you will like Keyboard Trigram or not is hard to predict. Your preference could depend on your approach to learning, practising, and possibly memorizing new music, or your openness for trying out something new. But one thing is for sure: if you don't put some time and effort into learning to read it, you will never know. That applies whether you are an expert, a beginner, or somewhere in between.

The benefits of learning music and the role of notation

Why learn to play the piano? For some people, it's what they have always wanted to do. But there are many other reasons.

The benefits of learning to play music are well known, and they apply no matter how old you are. Learning music can improve your mood, health, and well-being. It can also improve your non-musical learning ability in areas such as language or mathematics (these are called "transfer effects" in psychology). For young people, learning music might paradoxically help you to study for other school subjects, whereas for older people playing music can be seen as a treatment for dementia, or as an effective method to delay its onset.

Many children and adults hesitate to learn to play music because someone once told them they didn't have talent, or because their parents did not believe in their ability or devote time to supporting their musical development. Psychologists point out that, in fact and with very few exceptions, everyone has musical talent. Older people may think they are too old to learn something new, but again psychologists disagree -- learning continues throughout the lifespan and sometimes older people may even have an advantage, if they are more persistent.

Only a few percent of people are truly unmusical (Peretz & Hyde, 2003). Most who believe that they are "unmusical" are mistaken or misled (Ruddock & Leong, 2005). Many simply missed out on the right environment within which to flourish musically as children (Ruth & Müllensiefen, 2021). To overcome this widespread impediment to musical progress and success, people need to restore their belief in their musical potential. They need to experience their own musical success (Costa-Giomi, 2004).

That's where tablature comes in. Tablature is music notation for a specific instrument, such as guitar tablature. Musical amateurs and beginners often have trouble learning to read conventional clefs, leger lines, key signatures, and accidentals (sharps and flats). That evidently contributes to the high dropout rate. Conventional notation is hard to learn because its structure of lines and spaces does not correspond in a simple way to the structure of musical instruments. That is as true for the violin fretboard and the pattern of keys on a flute at it is for the piano keyboard. The problem is more serious for the piano because pianists play several voices at the same time, with two hands. Changing the notation system cannot solve all these problems, but it can facilitate learning and reading processes.

Learning any music notation system takes a lot of time and effort. Research suggests that people are motivated the enjoyment of music making. If that reward is lacking, they give up. That suggests a possible solution: people might persist longer if they could play more interesting music more quickly. Tablature makes that possible.

The question is timely for several reasons:

- The number of retired people is increasing. Most of them could benefit from musical activities (Varvarigou et al., 2012). We should be considering their needs and experimenting with new approaches.

- An increasing number of people of all ages are learning the piano from internet videos. Today's piano learning apps make it possible to learn pieces without necessarily reading conventional notation. The apps can even listen to what you play and let you know when you make a mistake.

- In the past few decades, music theorists have increasingly used methods based on the 12-tone chromatic scale (pitch-class set theory) to analyze tonal music and understand tonal musical structure. That suggests that notation systems based on the 12-tone chromatic scale are becoming more academically acceptable. Conventional music notation is based on the 7-tone diatonic scale.

What Keyboard Trigram leaves out, and why

To reduce clutter, Keyboard Trigram notates the start of each note but not its duration. That may come as a shock to some musicians, given the importance of duration for regular notation.

Music notation never specified everything about a performance. Imagine trying to perform a piece by Chopin without ever having heard a performance! Conventional notation is remarkably unspecific about note-by-note fluctuations in timing and dynamics (rubato and expression), or pedaling.

Things have changed a lot since the invention of sound recording, over a century ago. Today, the musical score is not the only source of information about classical piano music. Today's musicians and amateurs first get to the know a piece of music by listening to live or recorded performances. Only after that do they learn to play it.

The same applies for Keyboard Trigram. As you listen to a piece music, you will get an idea of the tone durations (e.g., whether detached/staccato or smooth/legato) as well as timing and dynamics. If you need more information about the durations of specific notes, or if you would like to know whether the note you are currently playing was notated C♯ or D♭, you can always check the original score. But your first task is to press the right keys at the right times, and Keyboard Trigram helps you to do that.

Are you an experienced pianist and skeptical about alternative notations?

There are good reasons to be skeptical. Many alternative music notations have been proposed and forgotten in the past couple of centuries. There is a book about it, and an international organization that is devoted to investigating and promoting notational alternatives. Among those notation systems were various kinds of keyboard tablature (e.g., Klavarskribo). A tablature is a form of notation that is designed with a specific instrument in mind, such as guitar tablature. But hardly anyone has heard of piano tablature.

Unlike earlier notation inventors, the inventors of Keyboard Tablature are not claiming that it is the best. Instead, we are claiming that, for the first time, an unlimited amount of piano music is available in an alternative notation system, due to the availability of midi files. You can download thousands of midi files from MuseScore Sheet Music Library. That makes it worthwhile investing the time needed to learn to read Keyboard Trigram, or any other notation system for which such an app is available. Moreover, Keyboard Trigram, is similar to other keyboard tablatures (such as Klavarskribo); if you learn one keyboard tablature, you can also learn another if it is based on the same basic idea.

While learning piano tablature, musicians will notice a problem. Sometimes a note in tablature looks similar to a note in conventional notation, but means something else. For example, the bottom line of the conventional 5-line treble clef is E, but the bottom line of a 3-line clef corresponding to three adjacent black keys is F♯ or G♭. If you are good at reading conventional notation, your mind might to jump to the wrong conclusion when you see that note. You will repeatedly have to correct that wrong conclusion, which is like undoing years of training.

But this problem is not as bad as it seems. To become an expert in any skill, you need very roughly 10,000 hours of practice (Ericsson, 2014). That is because people are competing with each other. There are only so many productive hours in a day, and only so many productive years in a lifetime. If you are an expert pianist, you could well have already spent 10,000 hours reading conventional notation. No wonder you are good at it!

The good news is that you won't have to spend 10,000 hours learning Keyboard Trigram. After about 10 hours you will be getting fluent, and after about 100 you will be able to read Keyboard Trigram as fluently as conventional notation. These numbers are no more than order-of-magnitude estimates, and of course everyone is different. The point is that learning Keyboard Trigram is in any case much easier than learning conventional notation, even if it doesn't seem easy at the start. A little patience goes a long way.

If you are planning to learn the piano from scratch, the time you will need to learn to read Keyboard Trigram is certainly much less than the time you would need to learn conventional notation to the same level of fluency. If it takes you 1000 hours to learn to read conventional notation fluently, you might need only 100 hours to learn to read Keyboard Trigram to the same level. These numbers are mere guesses, and again everyone is different, but they are probably in the right ballpark.

Can I become notationally bilingual?

Guitarists are often bilingual, reading both conventional notation and guitar tablature. In fact, guitar can be taught effectively by combining both systems (Thompson, 2011).

Our experience with keyboard tablature has been similarly positive. The opportunity to automatically generate a practically limitless library of musical scores in keyboard tablature means that it is worthwhile for pianists at all levels, from beginner to professional, to invest the necessary time and effort.

With practice, a staff of five lines looks quite different from a staff of three, so the two will not be confused, making bilingualism realistically possible. In both cases, fluency involves learning to recognize a large vocabulary of visual patterns and link them to musical elements, just as bilingualism in language is about learning many sound patterns and linking them to linguistic meanings. Like in language, music-notational bilingualism allows and encourages a musician to perceive musical structures in different ways and from contrasting perspectives, enriching cultural diversity. It is possible to become bilingual in two languages such as English and French despite the many misleading similarities between the two (false friends).

To become bilingual in Keyboard Trigram and conventional notation, you can either learn conventional first and trigram later or vice-versa. In both cases, the disadvantage of confusions between the notations (notational "false friends") will be outweighed by the advantage of each notation separately. The advantage of conventional notation is that it gives you access to practically all Western music for all instruments, whereas Keyboard Trigram allows you to quickly see relationships between musical pitch-time patterns and the piano keyboard.

You will notice when learning Keyboard Trigram that it gives you a different impression of the structure and content of the music. Your eyes are opened to a new perspective on musical structure. There is an interesting academic debate about what, if anything, enharmonic spellings (the difference between F♯ and G♭) tell us about musical structure (Parncutt & Hair, 2018). Enharmonic spellings may ultimately be a meaningless byproduct that arose from a long tradition of writing music on a staff designed for 7 rather than 12 notes per octave. If that is true, the meaning of regular tonal music for the listener depends only on pitch relative to the chromatic scale, and time relative to the meter. That is exactly what Keyboard Trigram presents to the reader.

A brief history of conventional music notation

Where did conventional European music notation come from? Why is it the way it is today? If you're interested in history, this section is for you.

Conventional music notation is a great cultural achievement. It was developed gradually over centuries, and is now used to notate almost any Western music.

Accidentals are an important aspect. Accidentals are symbols that change the pitch of a note. Sharps (♯) raise the pitch by a semitone and flats (♭) lower it. Sharps and flats remain in force until the next barline. If before that you want to return to the original pitch, you will need a natural (♮). Often, you will see a bunch of sharps or flats at the start of a line of music. This is the key signature, and it remains in force throughout the piece, or until a new key signature comes along.

When graphical music notation began in the 11th century, there were no accidentals or key signatures. Unaccompanied melodies in the 7-note diatonic scale (ut re mi fa sol la ti) were notated graphically on a staff, by putting some notes on the lines and other in the spaces. That’s how Gregorian chant was first written down. Previously, it had been learned by ear and passed on by imitation.

In the next few centuries, music became more complex. After a while, notation was representing all 12 notes of the chromatic scale relative to the original 7 notes of the diatonic scale. Key signatures were used when the music was based on scales that included black keys.

The notation we use today stabilized in the 18th century. Since then, it has been used to notate a staggering amount and variety of music, which demonstrates its enormously flexibility.

But conventional notation is not necessarily the best solution for all applications. Take the guitar. The relationship between what you see in a conventional guitar score and where you put your fingers on the fretboard is very complex. That is why a lot of guitarists use tablature, which shows more directly where to put your fingers.

Piano music has a similar problem. The relationship between what you see and what you do with your fingers is complex. If music notation had been designed with only piano in mind, it would have looked very different.

What’s wrong with conventional notation for piano?

Conventional notation has enabled an enormous variety of wonderful piano music to be composed and performed. Hopefully, it will continue to do so for a long time. But that does not necessarily mean it is the best way to write down piano music.

On the piano keyboard, the note C is always just to the left of the two black keys. It looks the same in every octave register.

Moreover, each note can be notated in at least two different ways, called enharmonic equivalents. The note C sharp (C♯) can be written D flat (D♭). The note C can be notated B-sharp (B♯), C-natural (C♮), or D-double-flat (D♭♭).

Combining the first problem with the second, we can generate 18 different notations for what is essentially for the same piano key:

All of these 18 representations of the note C (or its enharmonic equivalents) happen often in real music. The problem gets more extreme, the more complex the music gets.

If you think music notation is set in stone, these points may seem irritating. You will be thinking: "Why talk about changing notation when it cannot be changed?" But what if it can be changed?

Keyboard Trigram, step by step

Conventional music notation is sometimes called graphic because it is similar to a graph of pitch against time. Pitch is the vertical axis and time is the horizontal axis. Graphic music notation was invented in Italy in the 11th century.

Conventional music notation is also symbolic because it relies on symbols with special meanings. Pitch symbols include bass and treble clef symbols and accidentals (sharps, flats, and naturals). Time symbols include time signatures, barlines, and note durations (whole note, half note, quarter note, and eighth note – also called breve, minim, crotchet, and quaver, respectively).

A possible way to make music for piano easier to read is to make it more graphic and less symbolic – more like a graph. Pitch then corresponds more simply to vertical distance and time to horizontal distance. Notation inventors of the past did this in various ways, creating notations that we might call graphic keyboard tablatures.

Keyboard Trigram uses a three-line staff. A staff or stave is a group of parallel, equally spaced horizontal lines. The five-line staff of conventional music notation is sometimes called a pentagram.

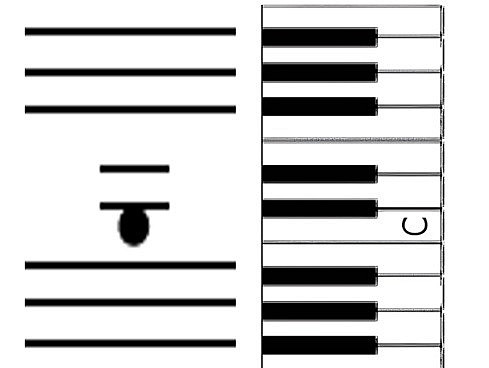

In Keyboard Trigram, the note C always looks like this:

The trigram corresponds to groups of three black notes on the keyboard. The short lines (called leger lines or ledger lines) are the groups of two black notes. On the keyboard, the note C is just to the left of the two black notes. In the notation, the note C is just under the two leger lines.

The full modern piano keyboard has just over 7 octaves, and it includes 8 Cs. The lowest C is called C1 and the highest is C8. In Keyboard Trigram, these 8 Cs all look the same. The note C always lies just below a group of two short leger lines. It always touches the lower of the two lines.

The barlines in Keyboard Trigram (the vertical lines between measures) cover roughly a four-octave range. They extend two octaves above and two below middle C, from C2 to C6, or more precisely from F#2 to B♭5. They allow you to orient yourself relative to the long piano keyboard.

Notating time and duration in Keyboard Trigram

Keyboard Trigram focuses on what most amateur pianists need to know: where to put your fingers on the keyboard, and when. To avoid clutter, we leave the rest out. Our notation nevertheless retains three aspects of conventional rhythm notation:

- We notate the start (onset) of each note with a notehead.

- The distance between the notes, from left to right, is proportional to the time difference. In other words, duration is notated graphically. (In conventional notation, horizontal spacing is approximately proportional to notated time; exact timing is notated symbolically, by different symbols for quarter note and half notes. This distinction is maintained in our notation "No. 2").

- We use barlines, but in a different way: barlines go through the middle of the noteheads at the start of each measure. (In conventional notation, barlines are slightly to the left of the first notes in a measure.)

Our notation does not tell you which hand should play which note, nor does it tell you which fingers to use. Conventional notation often does that by putting the music for the right hand on the upper staff and music for the left hand on the lower staff, but there are exceptions – think of Bach fugues in which the inner voices are played alternately by the left and the right hand. In any case, you can add fingerings to Keyboard Trigram scores in the usual way. Our tip: write right-hand fingerings above the noteheads and left-hand below, or write left-hand fingerings upside down.

You can add conventional rhythm notation to Keyboard Trigram No. 2 by hand by referring back to the original conventional score. Pianists may find this option useful when preparing a professional performance. One approach is to copy selected note stems, flags, beams, and phrase marks. Another is to mark the end (offset) of selected notes with tick marks (✓), which you can do with either No. 1 or No. 2. If you are working with a teacher, she or he will help you.

Is it ok to change a venerable musical tradition?

That's a misleading question. In fact, we are not changing conventional music notation. Instead, we are supplementing a venerable musical tradition with a new tool that will help to maintain it into the future. If more people learn to read classical piano music, despite the forward march of digital technologies, classical traditions will continue to flourish. Conventional notation will not be affected by piano tablature, just as it is unaffected by guitar tablature.

But some pianists are still skeptical. Conventional notation is what great composers used to write down their musical ideas. What would they have thought of Keyboard Trigram? In most cases, we will never know. But composers are usually creative, innovative, practical people. Many would have liked or approved of a project that helps people to play music that they could not otherwise have played. Composers like to experiment with new ways of doing things, which is what we are doing.

Some worry if it is ok to omit enharmonic spellings from music notation, like different notations for the same key on the keyboard (e.g. F# or G♭). Will something essential be lost if we don't know whether a particular note was originally notated F# or G♭? Musicologists and music theorists will answer this question differently, but that is not the point. The aim of keyboard tablature is not to reproduce all aspects of the original notation. The aim is to help piano players press the right keys in the right order.

There is also an aesthetic issue. Conventional music notation is beautiful, but beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Perhaps it is beautiful only because it is familiar (in general, we like familiar things) and because we associate it with beautiful music. If you dislike our Keyboard Trigram when you see it for the first time, perhaps it is simply unfamiliar. You need to learn to associate it the appearance of the notation with the sound of good music. Your perception will change as you start to use it.

About the author

Richard Parncutt is Professor of Systematic Musicology at the University of Graz, Austria. As a pianist, he holds a Bachelor of Music degree from the University of Melbourne. In the past, he performed many solo recitals and was a soloist with amateur orchestras in Melbourne and Armidale (NSW Australia) and Keele (England). As a psychologist, he has many frequently cited publications that address aspects of music psychology, often focusing on the perception of musical structure (see Google Scholar) and the psychology of piano fingering. He was a member of the Music Notation Modernization Association (MNMA) when it was founded in 1985 by Thomas Reed, and has carefully studied countless alternative notation proposals and the psychology of reading them.

Contact

Office and Library

Library Opening Hours:

Wednesday: 10am - 1pm

Friday: 11am - 2pm

Only during the semester, on days when there is teaching.